After all, what is the meaning of the term boteh?

Figalli Oriental Rugs consistently highlights the boteh design when it’s woven into any carpet in our collection. But what does this design signify? What’s its history? Why it enjoys global popularity? You’ll discover that the history of boteh is far more complex than its simple form implies.

Figalli Oriental Rugs consistently highlights the boteh design when it’s woven into any carpet in our collection. But what does this design signify? What’s its history? Why it enjoys global popularity? You’ll discover that the history of boteh is far more complex than its simple form implies.

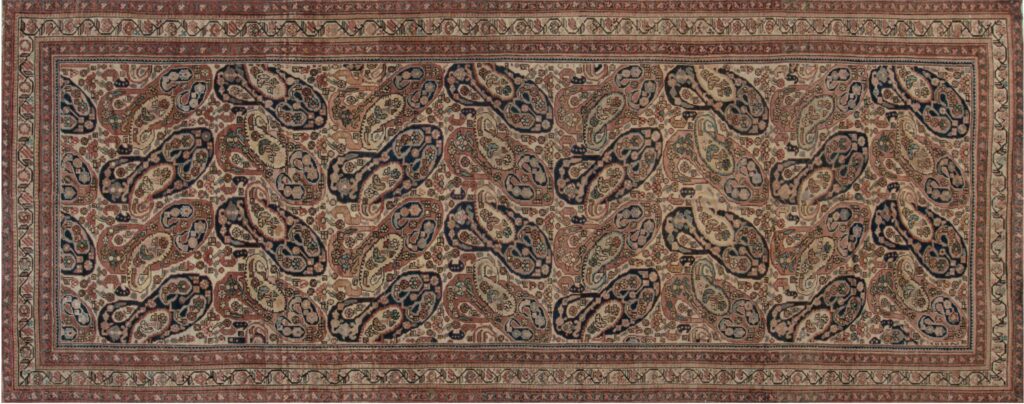

Boteh, a design that has evolved in various forms, has spread worldwide and continues to enrich the Persian and Indian artistic repertoire. From the simplest and minimalist form – a leaf-shaped design – to the most stylised and intricate, featuring various curvilinear botehs and different geometric shapes, this design has been reinterpreted for at least a millennium.

Traditionally, the boteh design resembles a curved teardrop, guiding the eye up and down, fostering a sense of balance. While there’s no standard format, the design elements remain the same, occasionally with an elongated and curved top, often housing an ornate design in the centre.

Malayer, 1900

Silk with Sassanid royal emblem depicting the wings of Homa or Senmurv, VI – VII centuries, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Although the term boteh or buteh translates in Farsi to a flower bud, leaf branches, or bush, the category carries deeper meanings. The boteh figure is often interpreted as a “seed,” suggesting the whole always exists within the part. The prevalent concept is that boteh symbolises new life sprouting from a tiny seed, referring to notions of fertility, renewal, and regeneration. However, its nature, identity, meaning, and place of origin remain subjects of debate among art scholars.

Other historians believe that in the arts produced during the final years of the Sassanids and the initial centuries of Islam, there was a symbiotic relationship between the cypress and the boteh forms, suggesting that this ancient design emerged from the cypress. According to a Zoroastrian tradition recorded by the poet Daqīqī, Zoroaster himself brought a cutting of a “noble cypress” (sarv-e āzāda). It was a gift to King Kayanid Goštāsp, who planted it as a memorial of his conversion to Zoroastrianism near the first fire temple (Āḏar-e Mehr Borzīn) in Khorasan. Thus, the boteh design is believed to represent a floral combined with cypress, a Zoroastrian symbol of life and eternity.

Relief at Persepolis Palace depicting a soldier from the Immortal Guard and the cypress

Built between the beginning of the 8th century and the first half of the 9th century AD, it is believed that the Noh Gunbad Mosque is the oldest building of the Islamic era in Afghanistan.

Numerous instances of the boteh design are found in both pre-Islamic and post-Islamic Iranian arts. However, no evidence links the boteh with Zoroastrianism. The earliest manifestations of this ancient design, primarily portrayed as the wings of the mythological figure Homa or Senmurv, were found in the arts of the Scythians and the Achaemenids, enduring until the Sassanid period. It’s confirmed that after Islam’s arrival in Persia, the boteh design permeated almost all Persian arts, appearing in ceramics, stucco, terracotta, metal, glass, textiles, and carpets. The boteh is visible in one of the oldest mosques, the Noh Gumbad Mosque (Masjid-i Haji Piyadah), built in the first half of the 9th century near Balkh (ancient Bactria) in Afghanistan. Despite time’s wear, much of the mosque’s rich arabesque decoration, made with clay bricks and covered with plaster, remains preserved. The columns’ surfaces feature arabesque carvings, and the floral medallions depict the boteh design.

The boteh underwent a status transformation in its long history and began to be used as a royal emblem (Farsi term: jegheh) during the mid-16th century Persian rule of the Safavid Dynasty. No longer an ornamental representation of the eternal cypress or related to immortality and timelessness, the boteh jegheh became a symbol of sovereignty and absolute power. Consequently, many Safavid paintings and fabrics feature the boteh jegheh as a distinctive mark of royalty on the crowns of kings and princes.

Once the boteh jegheh design became exclusive to the monarchy, its use beyond the court nearly vanished. Hence, the boteh jegheh does not appear on the royal carpets of the Safavid Dynasty. A royal object should not be stepped on or represented on an object placed on the ground. Thus, while the boteh jegheh continued to appear on the gold thread fabrics that royalty wore, it was absent from the carpets of this period of Persian history. However, textile artists of distant villages, unconcerned or possibly unaware of the boteh jegheh’s royal status, continued to employ this design in their carpets.

Boteh jegheh ornament on the Crown of Nader Shah Afshar, Emperor of the Safavid Dynasty, Persia (1688-1747)

Different variations of the boteh design on carpets

Shawl made of Kashmir wool. The central panel features a twelve-pointed star and four boteh designs with a folded tip. The outer edge also has botehs with the same shape and floral motifs.

Following the end of the Safavid period (circa 1736), the boteh design proliferated across the entire Persian territory, re-emerging in general arts and carpets. The form of the boteh evolved and migrated to other regions. By the late 17th century, it became a popular design in Mughal India (1526-1857), which maintained strong cultural ties with Persia. In northern India, the boteh, meaning flower in Hindi and Urdu, was primarily used in shawls woven with the fine wool of Kashmir, known as pashmina. This superior quality wool, composed of superfine threads of yarn from the mountain goats of the Himalayas, featured the first surviving examples of the boteh motif in Kashmir weavings from the 15th century AD. These were possibly commissioned by Sultan Zein-al-Aabedin, who introduced Persian designs to India. Since then, the motif has gained popularity among the wool shawls of Kashmir. During the Mughal period, the boteh design was reimagined with plant and flower representations, resembling a flowering and curvilinear bush, as seen in the shawl below.

In the first half of the 17th century, the British East India Company introduced shawls and other fabric items made in Kashmir to Europe. Britain led the manufacturing of women’s shawls using the boteh design when, in 1790 and 1792, the weavers of Edinburgh and Norwich began reproducing Kashmir shawls in only two colours, typically indigo and red. Paisley’s weavers in Scotland joined this burgeoning industry in 1805. In 1812, they used five different thread colours, giving Paisley’s weavers a competitive edge over weavers from other regions that used only two colours. Soon, the town name Paisley became synonymous with the boteh motif, and the demand for shawls grew as women across Britain began seeking ‘paisleys’. In Europe, boteh is referred to as paisley. From Britain, the boteh spread globally, becoming a universal design. It retains its luxury even in its simplest forms, presenting inherent and appealing art. While the boteh figure is still depicted in the shape of a teardrop, the design has also been recreated in more abstract versions.

After this extensive journey through the history of the boteh, it’s possible that this design holds different meanings and representations for people across various regions. One day, it may be possible to trace its history and transition from one empire, culture, and religion to another. Until new archaeological discoveries are made, the origins of the boteh and its meanings remain speculative. However, one thing is certain: the boteh is a captivating design. Now that you’re aware of its ancient roots, there’s a unique reason for you to appreciate the ancient carpets featuring this intriguing design. Figalli Oriental Rugs offers you magnificent pieces adorned with this enigmatic design.

Figalli Oriental Rugs

We do not sell rugs. We bring rare works of art to your home in the form of rugs.

Our services

You are Protected

Copyright © 2023 Figalli Oriental Rugs, All rights reserved. Desenvolvido por Agência DLB – Agência de Marketing Digital em Porto Alegre