Rugs Made for Royalty: The Superlative of Textile Artistic Expression

In Asia, rugs are woven works of art produced at all levels of society. Women have been weaving for centuries in villages throughout the Middle East and Central Asia. Their artistic creations were traded or made for personal use. Rugs served a utilitarian function and a visual expression of the artist’s mind.

However, rugs were also made in the courts of some empires. They were works of art that indicated the status and wealth of their owners. Rugs made for the court were used in the reception rooms of palaces, in the emperor’s audience chambers, and religious institutions supported by the court. Carpets produced in royal workshops were also given as gifts to other rulers. The illuminations of 16th and 17th century manuscripts show that smaller rugs were often placed on top of more oversized rugs and used in open areas such as pavilions and palaces.

Rulers had access to expensive materials, such as silk and metal-wrapped threads. They employed their empire’s most skilled artists, designers, dyers, and weavers to create palatial and luxurious rugs. Due to their quality, design, and mastery in execution, rugs of the courts are among the finest pieces of art in the oriental world. They are quite different from rugs made in commercial workshops or villages. Instead of employing only traditional motifs, court rugs often shared designs found in various media, such as in the paintings and illuminations of the manuscripts of the time.

Although rugs were made in many royal courts, the Ottoman (1281–1924), Safavid (1501–1732), and Mughal (1526–1858) empires provide the most exquisite examples of rugs produced for royalty.

Ottoman Court Rugs

The Ottoman Empire originated in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and was one of the largest and longest in the world. It controlled territories from North Africa to Eastern Europe between 1299 and 1923. Anatolia has a long tradition of rug making. However, in the 16th century, Ottoman court rugs began to feature specific designs created by the artists of the royal workshops. These designs were also used in the court’s ceramics, paintings, manuscripts, and fabrics.

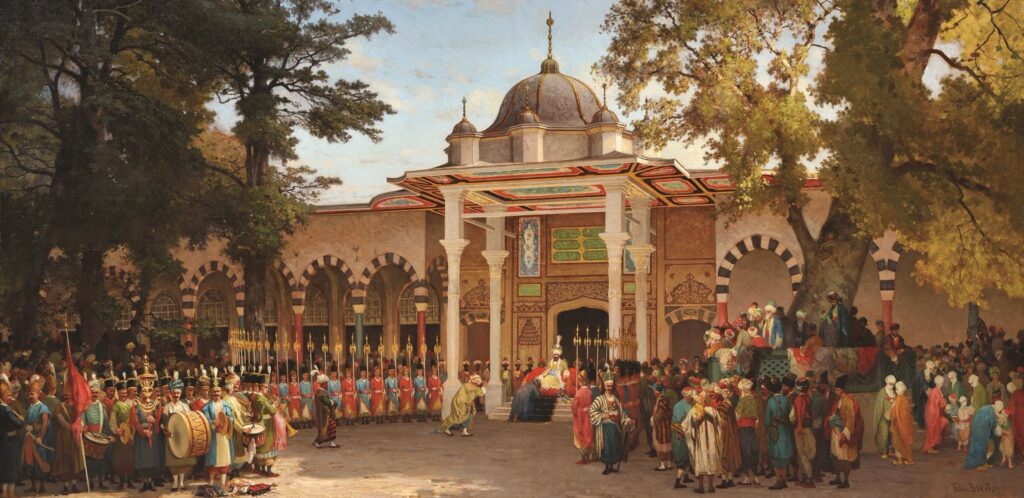

Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, Turkey

One of the most used designs was the “saz style”, made with long, sinuous leaves and stylized flowers. The court artists also developed the “floral style”, where we see more naturalistic representations of tulips, roses, carnations, and hyacinths. The floral and saz styles could be used as the only designs of the entire rug or were employed together with other motifs, such as the chintamani pattern (usually a combination of pearled circles accompanied by wavy lines, sometimes called “tiger stripes”), in a wide variety of objects designed by the court, including ceramics, silks, rugs, and manuscripts.

Ottoman court rug with cintamani pattern, 16th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This rug, made in the Ottoman royal workshops of the 16th century, features a wide border with large sequential flowers, framing the extensive surface of the carpet with the Chintamani design. A circular medallion occupies the centre, with a fleur-de-lis motif at its top and bottom, forming a vertical axis. The style of the central medallion and the four corner medallions is believed to have originated from the decorative bindings made on books.

The images below show the Ottoman court workshops’ use of the saz design. On the right, the detail of a splendid rug, with leaves in the saz design, stylized lotus flowers, and wavy cloud spirals, was made between the 15th and 16th centuries. Compare the saz design of the rug with the tile in the image on the left. This 16thcentury tile has various individual motifs, including a long-serrated leaf of the saz style that is overlaid with a white and red tulip and placed next to plum tree buttons and other floral medallions.

Both pieces are located in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

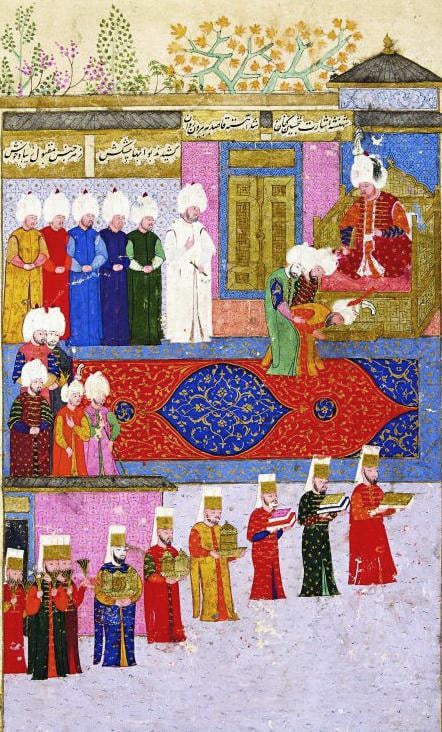

The illustrations of the manuscripts of the time show how rugs were used in the Ottoman court. In the painting below, commissioned by Sultan Murad III, a Safavid dignitary is observed being presented to the Ottoman sultan. As a backdrop, there is a magnificent Ushak rug in red and blue colours with a central medallion. The miniature shows how rugs were used as art and as rituals of power in the Ottoman court. In addition to creating a sumptuous setting for the ceremony held at the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, the rug sends a message to the Safavids (Persian dynasty rival to the Ottomans) about the wealth of the Ottoman court. A rug like this was used to demonstrate the Ottomans’ power, culture, and artistic achievements to court visitors.

Safavid Court Rugs

The Safavids ruled Persia from the early 16th century to the 18th century. Deep lovers of the arts, Safavid court rugs are known for their precision in the most minor details, the use of the best quality materials, and their sumptuous designs.

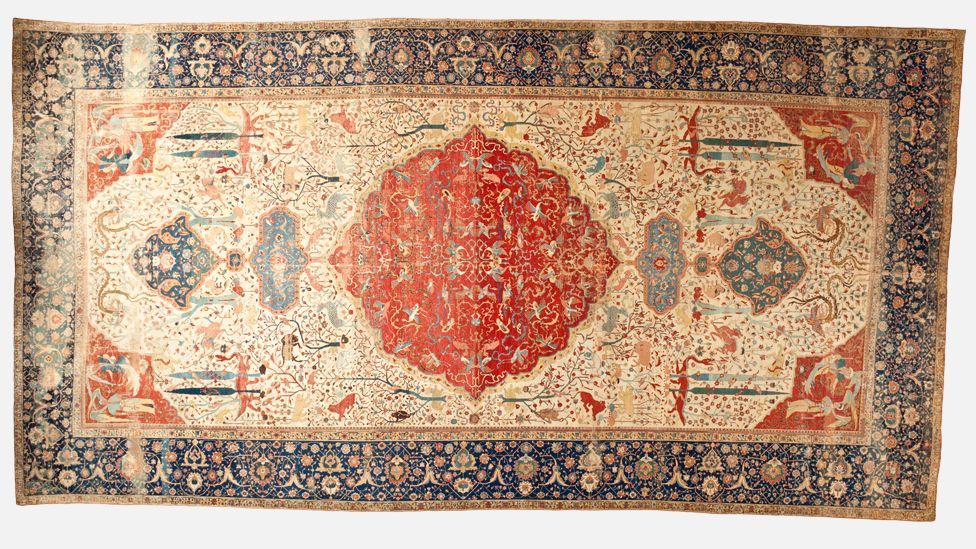

The rugs made for the Safavid court intended for formal environments such as religious institutions, for example, display non-figurative designs, such as vines, floral motifs, calligraphy, and shamsas (radiant sun), as is the case with the famous Ardabil rug. On the other hand, rugs made for more relaxed environments, such as those used in the palace pavilions, display a more comprehensive range of motifs, encompassing human figures, animals, and hunting scenes.

Central medallion (shamsa) of the Ardabil carpet (detail), made in the 15th century, Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

The image below is a remarkable example of a rug made for the Safavid court to be used in a less formal environment. It was woven entirely in silk, and its shimmering field is profusely rich in animal figures – some real, like lions and rams, and others fantastic. The animals, some of which are involved in intense combats, are situated amidst an exuberant setting of stylized flowers and trees. Hunting scenarios have always been popular in Persia. Since the early days of Persian history, hunting has been considered a pastime and a widely used theme in Safavid art until today.

Although the theme of the rug is hunting, its design presents a paradisiacal garden with abundant trees and animals. The smaller blue medallions show the water running through the park, which resembles interconnected pools. The dragons, the phoenix, the qilins (creatures from Chinese mythology), and especially the winged celestial beings, or huris, in each medallion confer a fantasy tone.

Rug details

Over the centuries, this masterpiece continued to be in the hands of nobility and royalty, although it was not necessarily used in informal environments. At the beginning of the 20th century, the rug was placed in Westminster Abbey on the occasion of the coronation of King Edward VII and became known as the “coronation rug”.

Painting of the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902, Westminster Abbey. The carpet is in front of the king’s throne. Today, this carpet is at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Mughal Court Rugs

The Mughals controlled much of the Indian subcontinent between 1526 and 1858, ruling a predominantly Hindu population. Belonging to a lineage from the Mongol dynasties of Central Asia, the Mughal dynasty soon established rug workshops in their courts.

The early Mughals employed Persian artists, so initially, Mughal rugs largely featured designs similar to the Persian tradition. Over time, a visual repertoire of Mughals was created exclusively for court rugs, miniature paintings, and other arts.

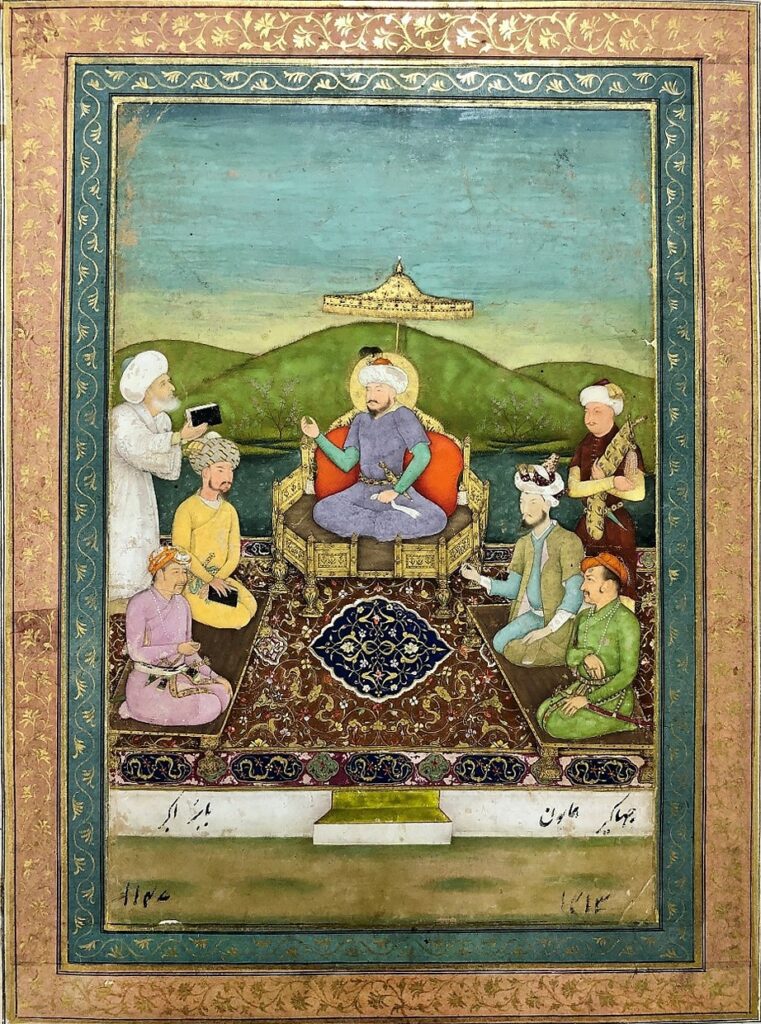

As with the Ottoman and Safavid courts, the designs of Mughal rugs contain direct parallels with manuscript illustrations. Among the representations of court life, rulers are expected to sit on finely executed carpets.

Emperor Timur seated on a carpet. 17th century Mughal miniature

Mughal dynasty rugs are pretty varied in their aesthetics. Naturalistic floral designs can be found in many Mughal court media. The peak of these arts occurred during the reign of Shah Jahan, the patron of the Taj Mahal. Following this tradition, this architectural wonder incorporates floral designs in its style.

Generally, the rugs feature detailed designs of plants and animals, reflecting these emperors’ interests in the natural world. It is common to find rugs featuring a lush and naturalistic vegetation scenario with various birds and other animals. Other rugs have a design of intertwined flowers with different floral motifs. Although natural and realistic scenes, hunting themes and historical records are frequent, Mughal art also comprises more abstract designs.

The image below is rug made for Emperor Shah Jahan. It is one of the four 17th century pashmina rugs in private hands. A masterpiece of the highest quality, it has the design of intertwined flowers. Even after more than four centuries, its colours and designs remain bright, having been made with the finest and most luxurious materials. The rug’s base is silk, and the pashmina pile is made from the mountain goat, the finest and most valuable hair.

Pashmina rug from the Mughal court of 1650. It was sold at Christie’s auction for £ 5,442,000 in 2022

Figalli Oriental Rugs

We do not sell rugs. We bring rare works of art to your home in the form of rugs.

Our services

You are Protected

Copyright © 2023 Figalli Oriental Rugs, All rights reserved. Desenvolvido por Agência DLB – Agência de Marketing Digital em Porto Alegre