The First Golden Age of Persian Carpets. The art of the Safavid Dynasty and its Legacy

The Safavid Empire (1501-1722), founded by Shah Esma’il I, swiftly conquered territories including Persia, Armenia, the Caucasus, Turkestan, and Afghanistan. The Safavids, deeply interested in arts, established schools in Tabriz and later in Isfahan under Shah Abbas. These schools taught ceramics, tile work, miniature painting, metal arts, silk brocade, velvet making, book arts, illuminations, manuscript illustrations, and carpet weaving.

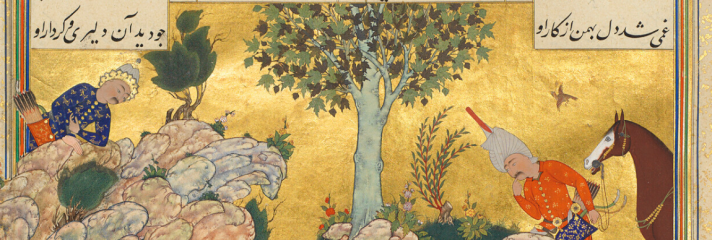

Three Safavid rulers significantly contributed to this period: Shah Esma’il (r. 1502-1524), his son Shah Tahmasp I (r. 1524-1576), and his grandson, Shah Abbas I (r. 1587-1629). Shah Tahmasp sponsored illuminated manuscripts, the most notable being the illuminations of the Shahnameh or Epic of Kings, written by Persian poet Ferdosi (940-1020). The illuminations by artist Aqa Mirak inspired many carpet designs during his reign. The world-renowned Ardebil carpet, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, was made during Shah Tahmasp I’s reign.

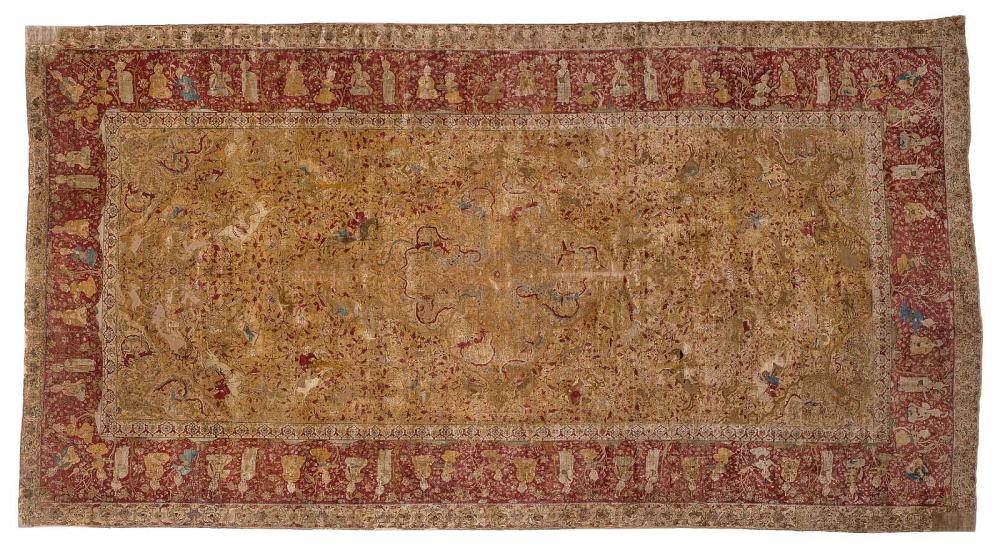

The image below depicts a carpet with hunting scenes and banquets, reflecting Safavid court life. The rug’s palatial size, superior silk material, and exquisite finish suggest it was made for Shah Tahmasp I. The rich pictorial patterns are believed to be the work of leading Safavid court painters, Aqa Mirak and Sultan Muhammad. The central medallion, adorned with metallic threads, depicts a battle between dragons and the phoenix, a motif showing Chinese influence in Persian art. The field’s flowering vines feature hunters pursuing rabbits, deer, antelopes, and lions. The border design’s relaxed atmosphere contrasts with the dynamic center, with elegantly attired courtiers discussing the day’s hunting adventures over food and drink.

Miniature painting of Shah Tahmasp I

Hunting rug made for Shah Tahmasp I around 1530. Property of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

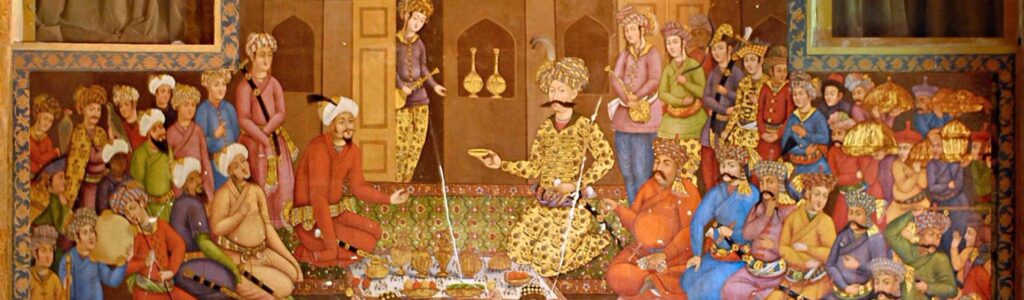

Painting of Emperor Shah Abbas I

In the late 16th century, Shah Abbas I relocated the Safavid Dynasty’s capital to Isfahan, transforming it into an architectural masterpiece and the empire’s crown jewel. Isfahan, a city of gardens, squares, palaces, mosques, and bazaars, was so beautiful it was dubbed ‘Esfahan nesfe-e jahan’ (Isfahan is half the world).

The ancient city of Isfahan or ‘half the world’

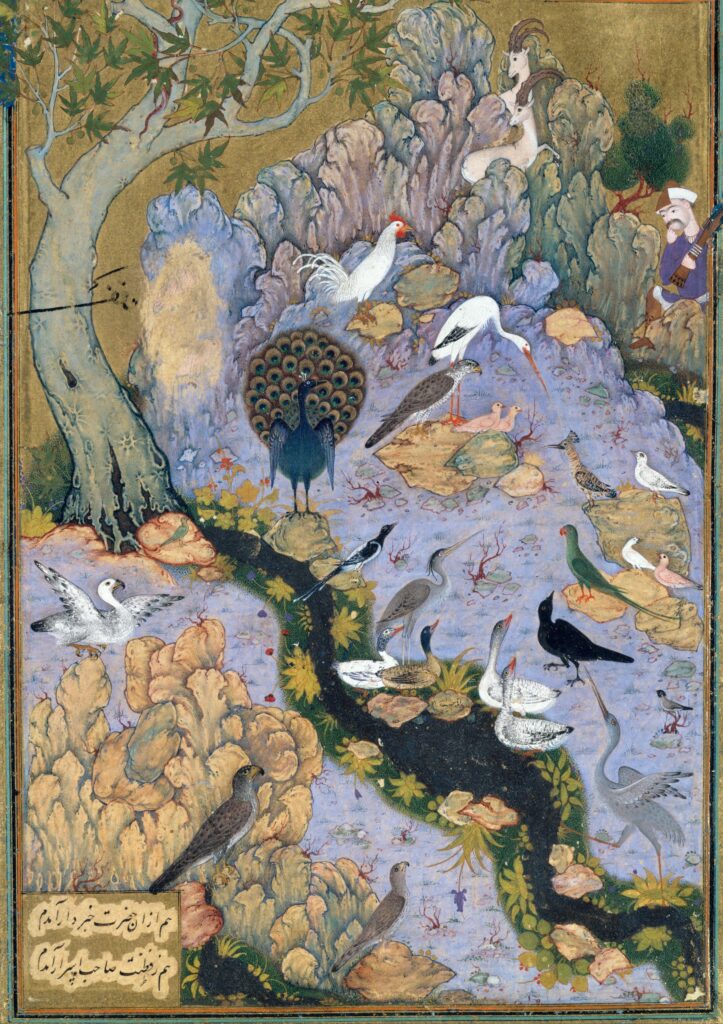

Page of the Mantiq al-tair manuscript illustrated with ink, opaque watercolor, gold and silver by the artist Habiballah of Sava around 1600.

During the 17th century, European clients sought Persian carpets with Polonaise, Vase, and Herat-Isfahan designs. The majority of orders were for Polonaise design rugs made with pastel and neutral colors and lavish motifs in silk and metallic threads. Many European noble carpets bearing the royal family emblem were ordered directly from the Isfahan workshops. The Safavids achieved an unparalleled balance between the composition and execution of carpet art by requiring their most talented artists to fully commit to design creation.

Alongside the Shah Abbas design, other figures like the lotus flower and peony flowers may appear in a carpet’s design. Distinguishing the Shah Abbas palm leaves from a peony or lotus flower can be challenging due to their artistic complexity. This design is prevalent in carpets from India, Pakistan, and China, signifying its global migration while retaining its connection with the Safavid Dynasty and Shah Abbas.

Another design legacy from the Safavid Dynasty is the central medallion, often containing animals, birds, or hunting figures ornamented with palm leaves and vines. Stylized human and angel figures and sometimes poems adorn the borders of some carpets.

Carpets from the First Golden Age of Persian Carpets revolutionized carpet production in Persia and other regions under Persian Empire influence. The Shah Abbas pattern, featuring large palm leaves, vines, and tiny flower buds, is the most renowned design from the Safavid Dynasty. This motif, often covering the entire carpet or surrounding a medallion, symbolizes the Persian Empire. Despite regional variations and artist modifications, the Shah Abbas design remains a popular motif in Persian rugs and carpets from other countries.

Alongside the Shah Abbas design, other figures like the lotus flower and peony flowers may appear in a carpet’s design. Distinguishing the Shah Abbas palm leaves from a peony or lotus flower can be challenging due to their artistic complexity. This design is prevalent in carpets from India, Pakistan, and China, signifying its global migration while retaining its connection with the Safavid Dynasty and Shah Abbas.

Another design legacy from the Safavid Dynasty is the central medallion, often containing animals, birds, or hunting figures ornamented with palm leaves and vines. Stylized human and angel figures and sometimes poems adorn the borders of some carpets.

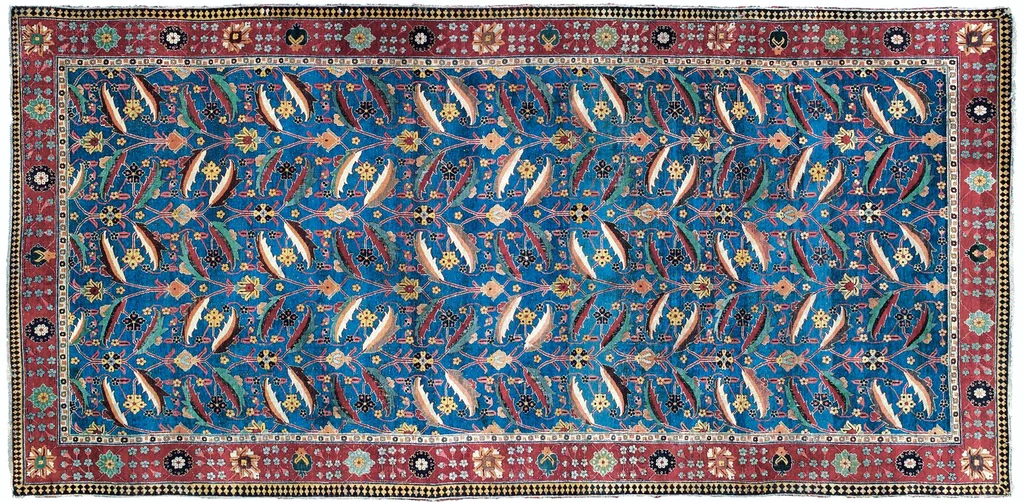

The Vase design carpets, primarily made in southern Persia’s Kerman, significantly influenced rugs made during the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th and 17th centuries. These Persian carpets feature floral designs overflowing from vases, filling the rug’s field with flowers and leaves intertwined by branches.

Crafted by skilled artists, these carpets captivate with their intricate designs and enchanting colors. The image below illustrates a mid-17th century vase design carpet from the Kerman region, showcasing an ultra-sophisticated design. The motifs and color harmony create a contrast that accentuates the artist’s chosen elements. This visual effect is achieved by dividing the leaves into three color areas. The carpet’s floral patterns are linked by spiral vines, imparting a sense of movement and an elegant geometric structure. Vase design rugs aim to emulate Persian court gardens. Over time, these designs permeated Persia and were adopted by other artists. These carpets continued to be produced throughout the 18th century, with evolving designs. In some instances, the vase is implied rather than explicitly depicted, while in others, it is extravagantly oversized.

Figalli Oriental Rugs

We do not sell rugs. We bring rare works of art to your home in the form of rugs.

Our services

You are Protected

Copyright © 2023 Figalli Oriental Rugs, All rights reserved. Desenvolvido por Agência DLB – Agência de Marketing Digital em Porto Alegre