Would You Pay £5,442,000 for a Rug? Yes!

On October 27, 2022, Christie’s auction house in London sold a rare Mughal imperial rug from around 1650 for over five million pounds. Why would someone pay such a hefty sum for a small antique rug?

This unique rug, once part of Emperor Shah Jahan of India’s court, is a never-before-auctioned masterpiece. It’s one of only four 17th-century pashmina rugs remaining in private hands. Louise Broadhurst, director of the Oriental Rugs Department at Christie’s in London, explains its high artistic value.

Pashmina rugs are extremely rare. Only eight 17th-century pashmina rugs from the Mughal empire, preserved in their entirety, are known, with seven housed in museums. Additionally, there are thirteen fragments of pashmina rugs, ten in institutional collections, two in unknown locations, and one (the rug in question) privately owned.

17th century Mughal emperor Shah Jahan

Mughal Pashima, 17th century

This rug, woven circa 1650, was commissioned for the court of Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor of the Mughal empire who ruled northern India from 1628 to 1658. An art enthusiast and patron, Shah Jahan funded royal rug workshops established by his grandfather, Akbar, in various locations including Fatehpur Sikri, Agra, Lahore, and Kashmir.

While silk is typically the most prized fiber in textile arts, pashmina, made from the hair of Himalayan mountain goats, held greater value during the Mughal era.

Pashmina rugs crafted during the Mughal empire, particularly in the 17th century, are among the world’s finest. A pashmina fiber, about one-sixth the width of a human hair strand, allows for intricate knotting beyond what the naked eye can see. A rug with a fine silk base and excellent pashmina knots enables the creation of exquisite curvilinear designs and detailed naturalistic representation. The lustrous pashmina wool, of such exceptional quality, was reserved for rugs of significant size commissioned by emperors.

This rug, woven with an average of 500 pashmina knots per square centimetre on a silk base, exemplifies the highest quality found in the mid-17th-century Mughal court. Originally approximately 4.4 meters long, it has been shortened to its current dimensions of 2.75 meters by 2.74 meters.

Indian artists, masters in dyeing, used pashmina, rich in lanolin, to create beautifully saturated colours. The rug’s colours, including a crimson red shade made from the kerria lacca insect, are deep and gleaming, maintaining intense saturation over centuries.

The rug’s design features diamonds outlined by leafy twisted trefoils, creating closed compartments filled with flowers such as lilies, sunflowers, and possibly celosias, on a field of deep, gleaming crimson red. The main border design showcases interconnected vines with floral motifs on a red background and contain small stylized clouds derived from Chinese tradition, framed by two smaller, identical borders filled with a continuous vine loaded with small leaves and flowers.

The weaver employed “shading”, a technique of juxtaposing close colours without an outline, avoiding a division in the design, and resulting in a sculptural or three-dimensional effect. This technique produced a sumptuous effect, enhancing the naturalism of the leaves and flowers with the sequence of light and dark green tones in the trefoil design (see the image below on the left).

A second technique, “colour blending”, involves weaving knots of two colours side by side, alternating like a chessboard design, to create the visual effect of a third shade. This technique, widely used in Indian rugs, enhances the impact of naturalistic representation and expands the artist’s colour range. The red petals of this rug effectively employ this technique, with the inner area of the flower in red made by juxtaposing the red knot with the white knot, and the outer space of the flower in pink created by juxtaposing the pink knot with the white knot. Each petal has an external outline in black, but internally, the colours of the red and pink petals merge due to the absence of the outline (see the figure below on the right).

These techniques fostered a perspective that amplified the naturalistic effect of each flower, aiming to emulate the visual effect found in watercolour collections that accurately depicted plants and flowers. These European-origin paintings inspired the production of court-used interior architecture and furniture, presenting a naturalistic design of flowers, much like this rug.

This masterpiece, a rare survivor from the art produced by Shah Jahan’s Mughal court, boasts vibrant colours and a sublime aesthetic. Crafted with pashmina and silk, the most luxurious and costly materials from an ancient rug weaving tradition, the rug showcases the artist’s unparalleled skill in colour blending and shading technique, producing a sculptural and three-dimensional effect of the naturalistic design. This extraordinary rug, a result of an exceptional combination of materials and skills, was created by a visionary designer and commissioned by a king with boundless resources and a love for arts and nature. It stands as a testament to unsurpassed quality and masterful execution.

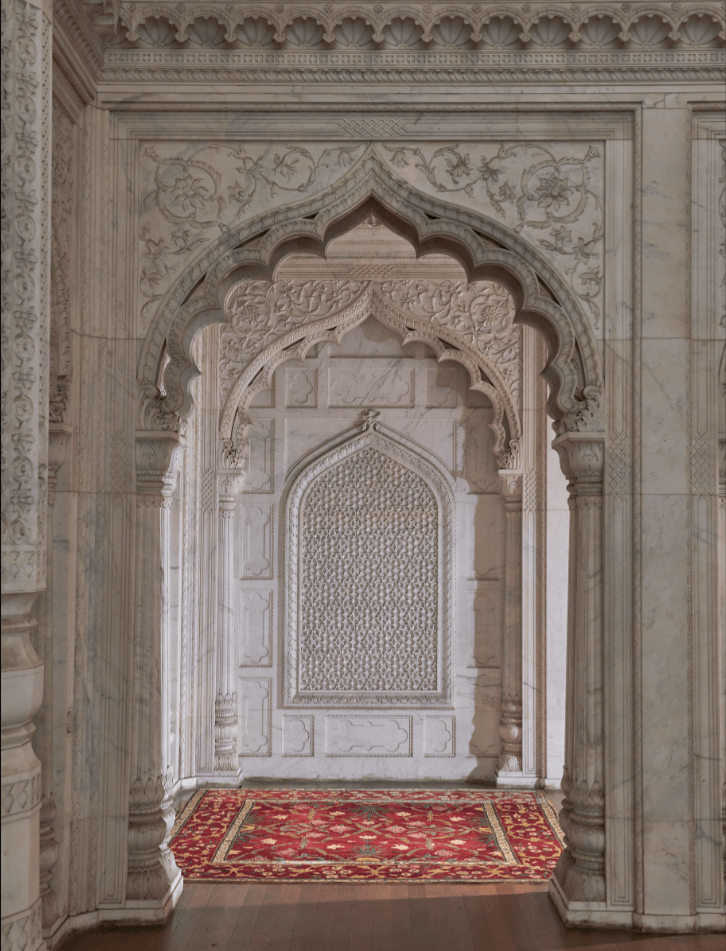

This rug was placed at the mansion of Elveden Hall in Suffolk, England, acquired in 1863 by Maharaja Duleep Singh, the final sovereign of the Sikh empire. The mansion’s interior was remodeled to mirror the Mughal palaces of his youth.

Figalli Oriental Rugs

We do not sell rugs. We bring rare works of art to your home in the form of rugs.

Our services

You are Protected

Copyright © 2023 Figalli Oriental Rugs, All rights reserved. Desenvolvido por Agência DLB – Agência de Marketing Digital em Porto Alegre